Inside the High-Stakes Bets That Broke Banks, Crushed Markets, and Made Fortune

The largest fortunes in finance didn’t come from playing it safe. They came from bold, high-conviction trades.

Many of these trades are made in the middle of panic, fraud, or chaos. They were made when most investors froze or ran for cover.

This is the history of traders who broke the pound, crushed short sellers, called the housing collapse, and turned market meltdowns into billions.

Each of the 11 trades below shares one trait: real risk. Livermore shorted the market before the 1929 crash and made over a billion dollars.

Soros and Druckenmiller bet against the entire British banking system and forced a currency to collapse overnight.

Porsche squeezed Wall Street’s smartest funds in the middle of the global financial crisis, and Jim Chanos proved Enron was rotten before anyone else dared to say so.

1. Jesse Livermore: Shorting 1929 Crash

In 1929, Jesse Livermore saw stock prices trading at extreme valuations, fueled by margin debt and rampant speculation.

Livermore used over 100 brokers to build short positions in major Dow stocks. He did this to hide his position.

When panic selling began in October, prices collapsed. Livermore bought back shares at lower prices, closing his shorts.

His profit totaled about $100 million, over $1.5 billion in today’s money.

Livermore’s strategy required leverage, discretion, and speed. The trade remains one of the largest short profits ever made.

Figure 1. Dow Jones Industrial Average from 1923 to 1933. The 1929 peak and subsequent crash mark the period of Jesse Livermore’s historic short trade. Source: www.taprofessional.de

Livermore acted without the benefit of modern information. No Bloomberg terminal. No real-time tape.

Still, he coordinated a bear raid at a scale Wall Street had never seen.

His timing was surgical. He started building shorts in September, weeks before the crash, waiting for the market to buckle.

As brokers called in margin loans, forced sellers accelerated the plunge.

After 1929, new regulations emerged. The SEC banned many tactics Livermore used, including short pools and secret syndicates.

2. Paul Tudor Jones: Black Monday 1987

Paul Tudor Jones saw signals of a major stock market top in 1987. He noticed that 1987 was mirroring the price action from before the 1929 crash.

Index valuations were stretched, volatility was rising, sentiment was euphoric, rising leverage, and the market’s upward momentum was fading.

Jones responded by building a large short position in U.S. stock index futures.

He added to the position as downside momentum increased. On October 19, when selling accelerated, his short futures bet paid off as the market lost 22% in a day.

Jones turned this sequence into a $100 million profit and a 125% return for his fund.

Figure 2. 1987 Black Monday crash, where stocks lost nearly 25% in a single session. Source: Investopedia.com.

Jones and his team built charts by hand and overlayed 1929 and 1987 to spot repeating price patterns.

They ran scenario analysis in a pre-Excel world and relied on discipline over technology.

He used what he called a “five-to-one risk/reward” rule. For every dollar at risk, he looked for five in potential gains.

This forced him to size up only when odds were stacked in his favor.

3. George Soros: Short GBP, 1992

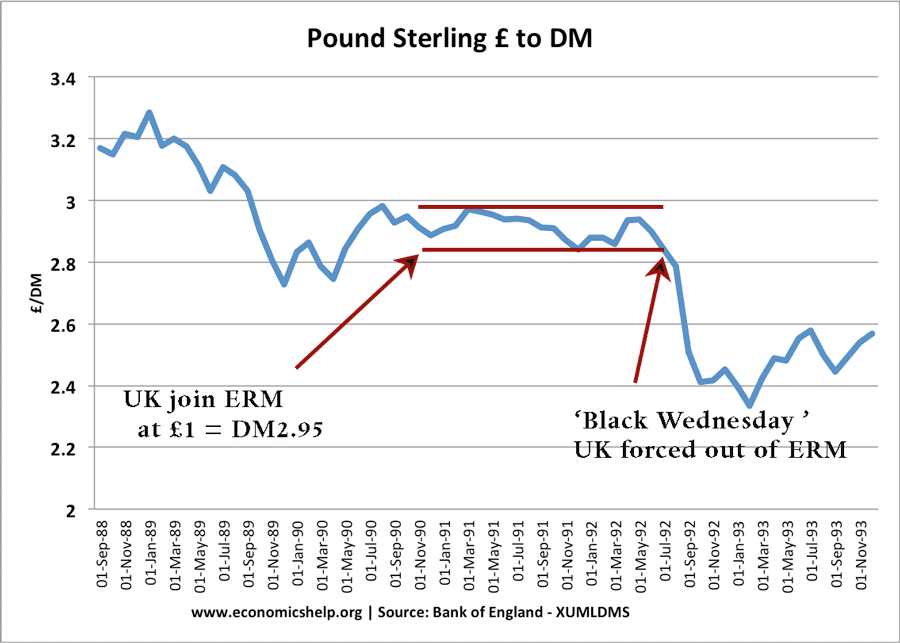

Soros and Druckenmiller saw that the British pound was overvalued because the UK had joined the European Exchange Rate Mechanism.

UK inflation was high. Growth was weak. The Bank of England kept interest rates artificially high to support the pound.

They realized this setup couldn’t last. Sooner or later, the UK would have to let the pound fall.

Druckenmiller proposed a large short on the pound. Soros pushed to go even bigger.

They borrowed billions of pounds and sold them for Deutsche marks, betting the UK couldn’t maintain the peg.

On September 16, 1992, the Bank of England gave up and devalued the pound.

The currency crashed, and Soros’s fund bought back pounds at much lower prices. The profit was about £1 billion.

Figure 3. Pound sterling vs. Deutsche Mark, 1988–1993. The chart highlights the collapse of the pound on “Black Wednesday” as the UK exited the ERM, Source: Bank of England / economicshelp.org.

Soros’s conviction came from a mix of macro analysis and real-time pressure testing.

He watched the UK’s foreign reserves bleed out as the Bank of England defended the currency.

When authorities tried to hike rates and intervene, Soros doubled down.

Druckenmiller used charts of historical currency pegs breaking, France, Italy, even previous UK devaluation, to estimate the likely fallout.

Technical analysis showed downside momentum building. Volatility spiked and volumes soared as speculators joined the attack.

Soros’s execution was bold. He wasn’t first, but he was largest. By betting bigger than anyone else, he forced the central bank’s hand.

4. Louis Bacon: Gulf War Macro, 1990

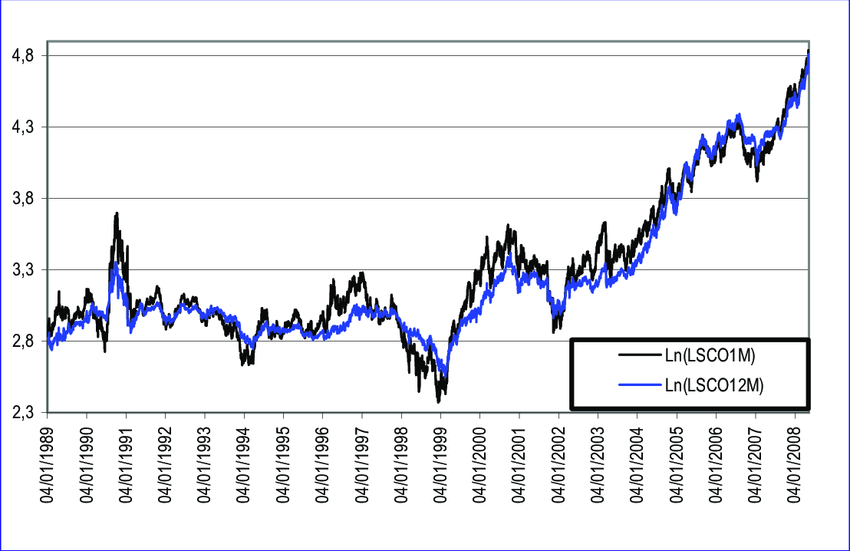

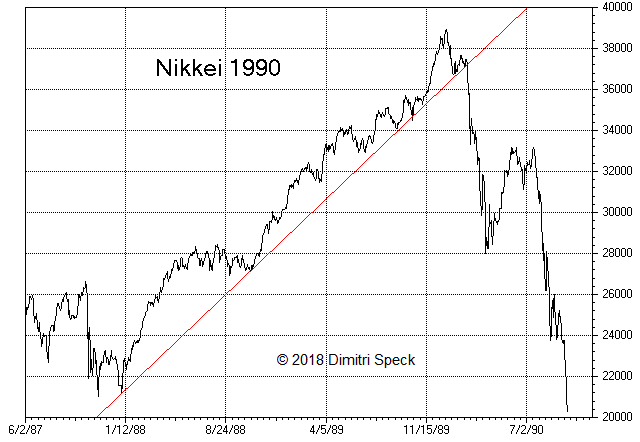

Louis Bacon spotted two key risks in 1990. Iraq invaded Kuwait, pushing oil prices higher.

At the same time, Japan’s stock market was peaking after years of rapid gains.

Bacon took a long position in oil futures, betting prices would spike as the Gulf War escalated.

He also shorted the Nikkei index, expecting Japan’s asset bubble to burst.

Both trades hit. Oil soared on supply fears, and the Nikkei collapsed as the bubble popped. Bacon’s Moore Capital fund finished the year up 86%.

Figure 4. Left: Crude oil futures prices spiked in 1990 as the Gulf War began. Right: The Nikkei peaked in late 1989 and crashed through 1990 as Japan’s asset bubble burst. Sources: ResearchGate, Investing.com.

Bacon’s strength lay in connecting global events before consensus formed.

He tracked geopolitical headlines and watched tanker data in real time, knowing that even a rumor could move crude markets overnight.

His edge was speed. Bacon acted before others digested the news.

He scaled positions with tight risk controls, ready to reverse if the war de-escalated or markets stabilized.

Bacon rarely gave interviews, but in his rare public comments, he credits his success to staying flexible, thinking in probabilities, and always watching the next catalyst.

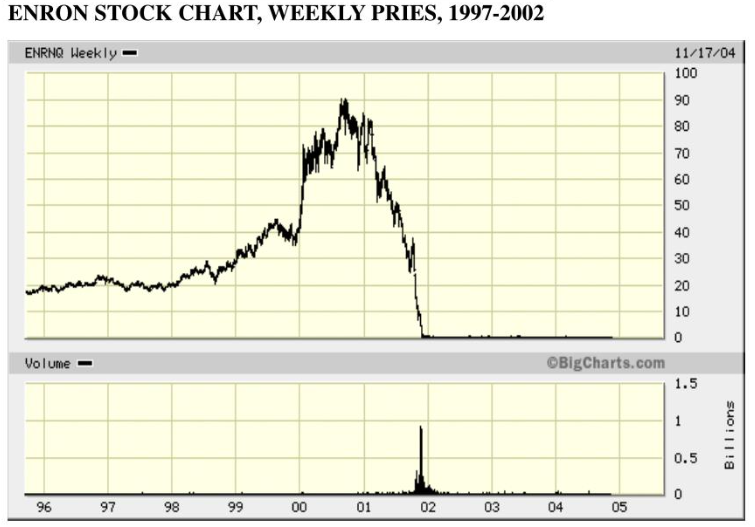

5. Jim Chanos: Short Enron, 2000–2001

Jim Chanos started digging into Enron’s financial statements in 2000. He noticed red flags, e.g. low returns on capital, confusing off-balance-sheet entities, and strange accounting for profits.

While Wall Street remained bullish, Chanos built a short position in Enron stock. He believed the company was hiding losses and inflating earnings.

When more accounting irregularities surfaced in 2001, Enron’s stock collapsed from over $90 to almost zero.

Chanos’s fund made about $500 million as Enron went bankrupt.

The trade set a new standard for forensic short selling and proved that careful research can expose even the market’s most hyped companies.

Figure 5. Enron’s weekly stock price from 1997 to 2002. It peaked near $90 in 2000 before collapsing to zero as the company’s fraud was exposed. Source: slideserve.com.

Chanos dissected Enron’s footnotes, searching for mismatches between reported profits and real cash flow.

He spotted that “mark-to-market” accounting let Enron book imaginary gains from long-term contracts.

He watched management unload stock even as they promised growth.

He tracked growing debt hidden in off-balance-sheet vehicles, signs the business was a shell game.

For over a year, he faced ridicule as analysts upgraded Enron and the media called it “the most innovative company in America”.

6. Burry, Paulson, Bass: “Big Short” CDOs, 2007

While most of Wall Street believed housing prices could never fall, Burry reviewed the actual loan documents behind mortgage-backed securities.

He found pools full of subprime loans, adjustable rates, no income verification, and high default risk.

Burry realized that when interest rates reset, these mortgages would collapse.

Burry started buying credit default swaps in 2005, betting that these bonds would fail. Few even knew what these swaps were at the time.

John Paulson and his team spotted the same flaws in subprime lending and built enormous CDS positions to profit from the crash.

Kyle Bass also raised capital, analyzed raw mortgage data, and saw the whole financial system was dangerously overleveraged.

When the U.S. housing bubble burst in 2007, mortgage-backed securities imploded. The swaps soared in valu.. Burry’s fund returned nearly 500%.

Paulson made about $15 billion. Bass’s fund delivered massive gains as well.

Figure 6. Subprime mortgage originations exploded from 2003 to 2006, with securitized loans reaching record highs and accounting for nearly a quarter of all U.S. mortgages. Source: Inside Mortgage Finance.

Burry’s edge came from first-principles analysis. He read thousands of pages of prospectuses, reconstructing the credit risk in each deal.

He built his own default models and showed that even small increases in foreclosures would crush the AAA tranches.

Wall Street banks dismissed him as crazy. Dealers were happy to sell CDS to anyone, since it was considered “free money”.

Burry held on, even as his investors doubted his sanity and withdrew capital.

Paulson took a different route. He hired mortgage specialists, sourced raw loan data, and ran Monte Carlo simulations to estimate worst-case losses

When subprime delinquencies spiked, he doubled down.

Kyle Bass spotted that banks held far less capital than their exposures required.

He published detailed memos and flagged systemic risk, years before regulators or ratings agencies responded.

7. David Tepper: Long Banks, 2009

In early 2009, most investors saw U.S. banks as untouchable. Stocks like Bank of America and Citigroup traded at pennies on the dollar.

The market expected total collapse or government takeover. David Tepper saw something different.

He noticed signs that the U.S. government would do whatever it took to prevent a banking failure, e.g. massive bailouts, TARP funding, and public support for the biggest lenders.

Tepper studied the balance sheets and calculated that, if the banks survived, their equity was wildly underpriced.

He started buying distressed bank stocks in size. While others dumped shares out of fear, Tepper loaded up on financials at their absolute lows.

As government rescue plans took hold and panic faded, bank stocks rebounded hard. By year’s end, Appaloosa Management was up about 120%.

Tepper personally made around $4 billion. This trade became a textbook example of buying when everyone else is terrified.

Figure 7. Financial sector ETF (XLF) forming a reversal pattern after the 2008–09 crash. Source: TheStreet.

Tepper’s process combined nerve with credit analysis. He read every detail in bailout terms, stress test results, and Fed speeches, looking for any sign of official support.

He noted when the Fed guaranteed bank debt and the Treasury injected fresh capital, evidence that policymakers wouldn’t let systemically important banks fail.

He didn’t just buy stock. Tepper built positions in preferred shares and bank debt, targeting the spots with the best asymmetric upside if the sector stabilized.

His conviction set him apart. Tepper appeared on CNBC mid-year and spelled out the thesis, saying bluntly,

As fear receded, the market caught up to his analysis.

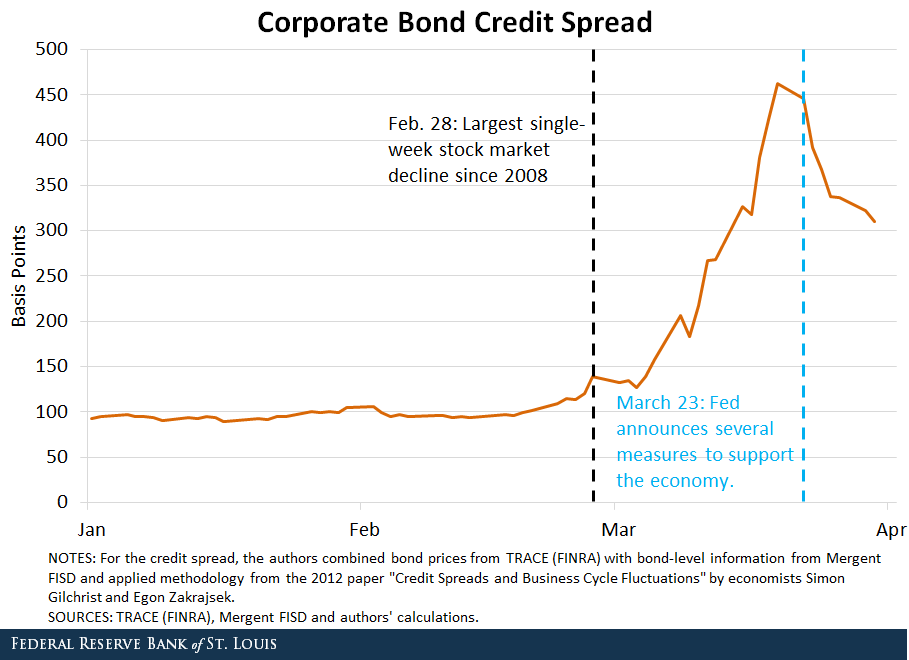

8. Bill Ackman: COVID Credit Hedge, 2020

In February 2020, as COVID-19 cases began to climb worldwide, Bill Ackman saw a risk few others were acting on.

He recognized that a global pandemic would crush corporate earnings and could trigger a credit crisis.

Ackman spent $27 million to buy credit default swaps on investment-grade and high-yield bond indexes.

These contracts would surge in value if companies started defaulting or if credit markets seized up.

As the pandemic spread and markets panicked in March, credit spreads exploded.

The value of Ackman’s hedge skyrocketed. In less than a month, he closed the trade for a $2.6 billion profit. A return of 100x.

Ackman then used the proceeds to buy stocks near the market bottom and doubled down when most investors were still running for the exits.

The trade showed the power of using cheap, asymmetric hedges to protect capital and profit during a once-in-a-generation crisis.

Figure 8. Daily corporate bond credit‐spread index from late Feb to April 2020. Source: St. Louis Fed.

Ackman’s insight came from watching early case growth in Asia and Europe and mapping out second- and third-order effects.

He tracked rising hospitalizations, supply chain shocks, and falling demand across industries.

The market was slow to react, still pricing in a short-lived disruption.

Ackman’s choice of CDS indexes meant the bet was liquid and scalable.

By focusing on broad credit indices instead of single names, he could hedge the entire portfolio without betting on individual bankruptcies.

Risk was capped and returns were asymmetric, classic tail-risk hedging.

If the market stabilized, he’d lose only the premium. If credit spreads widened, the payoff was exponential.

When the Fed intervened and fiscal stimulus arrived, Ackman locked in gains. He called the trade “the single best of my career”.

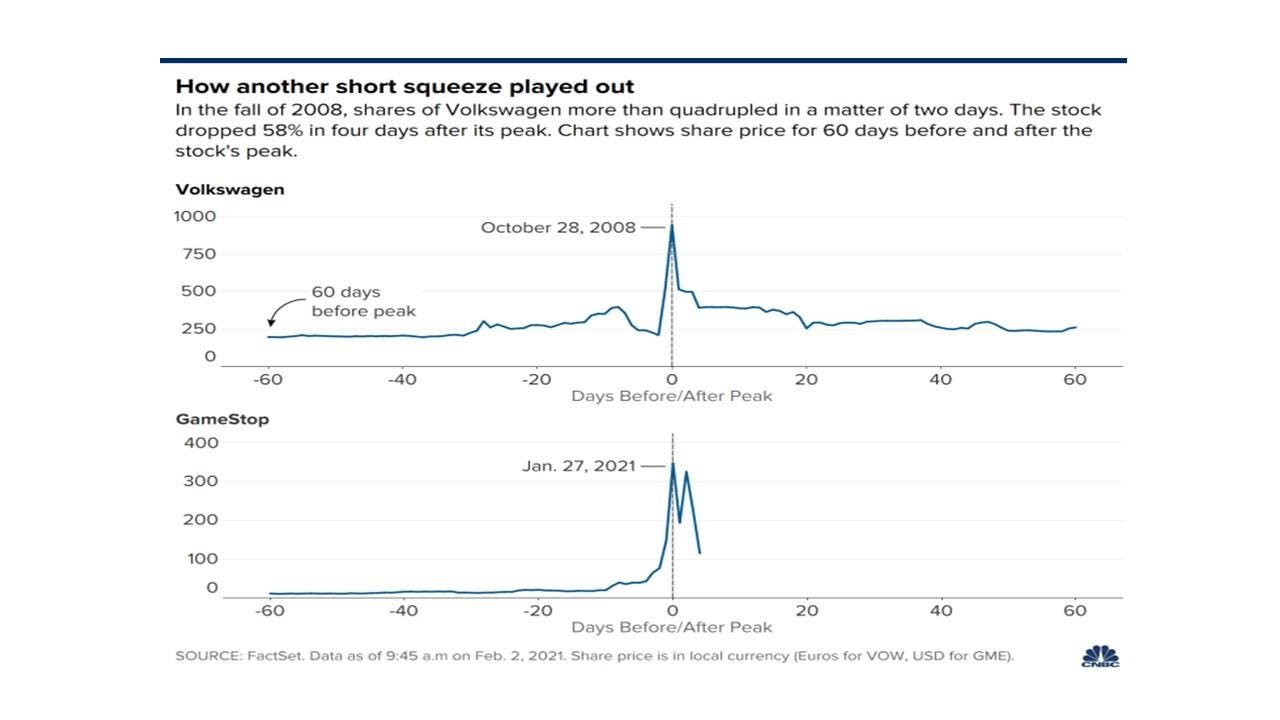

9. Porsche: VW Short Squeeze, 2008

In 2008, Porsche quietly built a controlling stake in Volkswagen by buying both shares and cash-settled call options.

Hedge funds, thinking VW was overvalued, aggressively shorted the stock, betting its price would fall during the financial crisis.

Porsche waited until October to reveal it controlled 74% of VW’s voting shares, far more than the market realized.

This left only a tiny fraction of shares actually available for trading.

Short sellers rushed to cover their positions, but there weren’t enough shares to buy back.

VW’s share price spiked from €200 to over €1,000 in just two days, briefly making Volkswagen the world’s most valuable company by market cap.

Porsche then sold some of its stake at these inflated prices, locking in a reported profit of €6.8 billion.

The VW short squeeze remains the largest in history and a warning of what can happen when market liquidity disappears.

Figure 9. VW shares surged from around €210 to over €1,000 within days in late October 2008. Source: Market Realist via CNBC.

Porsche’s strategy was very precise. They used derivatives to mask their true exposure, sidestepping disclosure rules and blindsiding the market.

Most analysts underestimated Porsche’s intentions, seeing them as a minority investor, not an acquirer.

The setup was classic: massive short interest and a shrinking free float. At the squeeze’s peak, short positions totaled more than the available shares.

Funds faced forced liquidations as losses snowballed. Prime brokers called in margin, and a desperate scramble for shares sent prices vertical.

Regulators and politicians demanded answers, but Porsche argued their actions followed the letter of the law.

The chaos forced Germany to tighten disclosure rules around derivatives and stake-building.

For hedge funds, the episode was catastrophic, some lost billions in days. For Porsche, the windfall nearly financed their attempted takeover of VW.

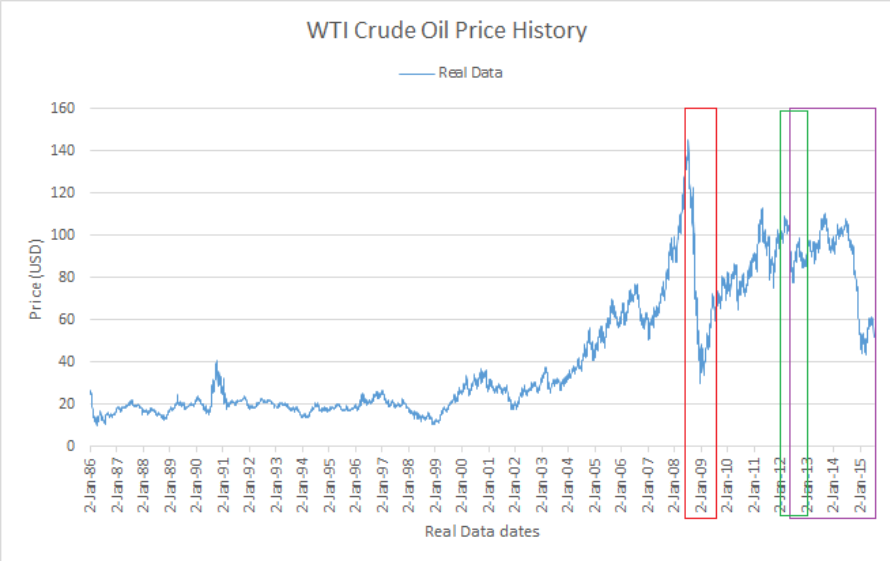

10. Andrew Hall: Oil supercycle (2003–2008)

Andrew Hall, head of Phibro (Citigroup’s commodity trading arm), saw a major shift coming in the global oil market.

In the early 2000s, he noticed rising demand from China and India, limited new supply, and years of underinvestment in production.

Hall believed oil prices would break out of their historic $20–30 per barrel range.

He built massive long positions in oil futures, locking in contracts years out at what he saw as bargain prices.

Hall often held his positions through volatile swings and continued betting that fundamentals would eventually push prices much higher.

From 2003 to 2008, oil surged from around $30 to nearly $150 a barrel. Hall’s trades generated billions in profit for Phibro and earned him annual bonuses as high as $100 million.

His conviction in the oil supercycle proved right when almost everyone else expected a return to lower prices.

Figure 10. WTI crude oil price history from 1995–2015, with the 2003–2008 period highlighted. Source: ResearchGate.

Hall tracked global inventory levels, shipping flows, and refinery bottlenecks, building a macro thesis supported by granular market intelligence.

He read obscure reports and called industry contacts, always searching for early signs of tightening supply.

Hall’s edge was patience and scale. He built positions in the far end of the futures curve to secure cheap supply while others focused on short-term price swings.

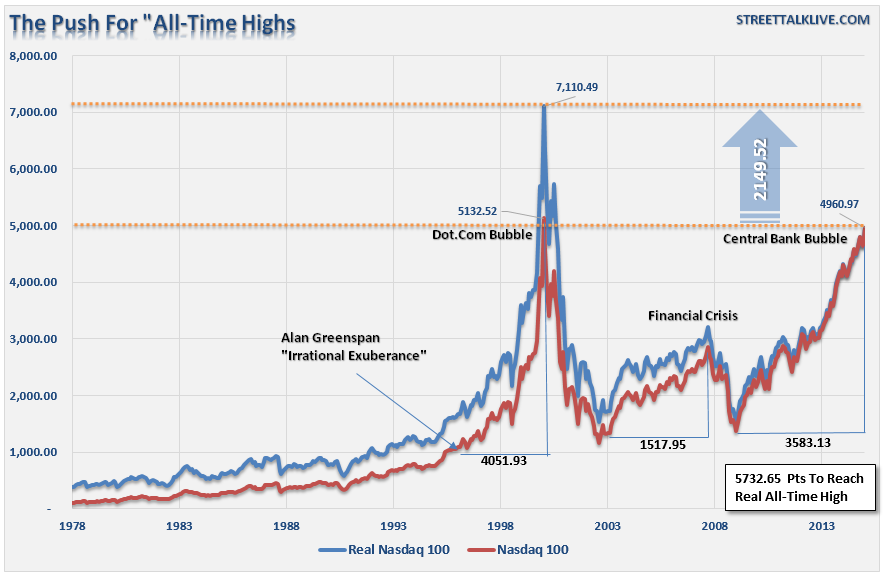

11. Robert Citrone: Tech Bubble (2000):

Robert Citrone, founder of Discovery Capital, saw the warning signs as the tech bubble inflated in the late 1990s.

He tracked soaring valuations, unsustainable business models, and companies with no profits being bid up to massive market caps.

Citrone did the work. He dug into company filings and balance sheets, identifying the weakest tech stocks and the most overhyped names.

He built short positions in these companies and in tech-heavy indices like the NASDAQ.

When the bubble burst in 2000, tech stocks collapsed. The NASDAQ dropped nearly 80% from its peak.

Citrone’s shorts delivered huge gains while the broader market suffered massive losses.

His fund outperformed nearly all peers that year, proving the value of research, skepticism, and betting against the crowd at the right moment.

Figure 11. NASDAQ Composite vs. S&P 500, 1995–2002: Tech stocks exploded to over 5,000 by March 2000 before collapsing nearly 80% by late 2002. Source: ResearchGate.

Citrone’s approach was forensic and unflinching. He created spreadsheets of key financial ratios such as price-to-sales, cash burn, debt levels and ranked tech companies by fundamental risk.

He tracked insider selling and secondary offerings, noting when founders and VCs cashed out near the top.

Citrone paired his single-name shorts with index puts and NASDAQ futures, to create a diversified bet against froth.

He didn’t try to time the top perfectly; instead, he built conviction as warning signs multiplied, e.g. IPO mania, speculative option buying, and magazine covers touting “the new economy”.

Honorable Mentions

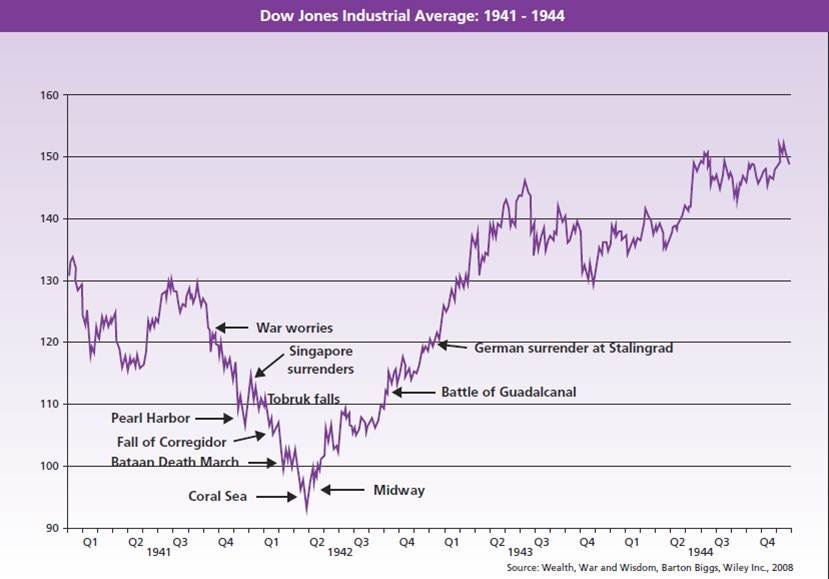

John Templeton: Buying the Bottom in World War II

In 1939, as World War II broke out, fear ruled the markets. Most investors expected years of economic pain. Templeton saw opportunity in the panic.

Templeton borrowed $10,000 and bought 100 shares of every NYSE-listed stock trading below $1, including dozens of companies facing bankruptcy.

He believed that not all these companies would fail, and that some would rebound as the war economy took shape.

Many of Templeton’s picks recovered or merged with stronger firms as the war progressed. Within four years, his investment multiplied fourfold.

Figure 12. Dow Jones Industrial Average (1941–1944), which shows the May 1942 “point of maximum bearishness”. Source: InvestmentOffice.

Richard Dennis: Turtle Trading (1980s)

Richard Dennis believed trading success could be taught. In the early 1980s, he ran an experiment.

He recruited a group of novices, known as the “Turtles”, and taught them a simple, rules-based trend-following strategy.

The system used mechanical signals: buy futures when prices broke out above a set range, and sell when they dropped below it.

Dennis gave each Turtle real capital and strict risk management rules. They traded a wide range of commodities, currencies, grains, metals using the same method, no matter the market.

Over the next few years, the Turtles turned small starting accounts into millions. Many doubled or tripled their capital within months.

Collectively, they made over $100 million in profits. Dennis proved that disciplined execution and sticking to tested rules can beat the market.

Figure 13. urtle Trading breakout system applied to crude oil futures. The buy signal is triggered as price breaks above resistance and the moving average. The sell signal appears when price closes back below the trend line. Source: Source: TradingView/BrandonBeylo.

Newsletter